1 of 3

Back in time

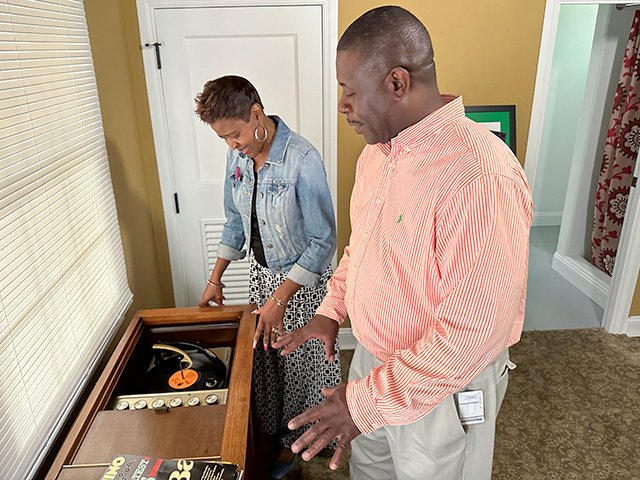

Mary “Cookie” Goings and Matthias Grissett of the Myrtle Beach Neighborhood Services Department explore a renovated motor lodge room at Charlie’s Place, a 1950s music hotspot that’s been renovated into a living history attraction.

Photo by Keith Phillips

2 of 3

Movers and shakers

Sarah and Charlie Fitzgerald owned many thriving businesses in Myrtle Beach, but the Whispering Pines Supper Club and the Fitzgerald Motel combined to make Charlie’s Place the beating heart of the segregated Booker T. Washington neighborhood.

3 of 3

Past and present

Matthias Grissett sits next to a mural-sized photo of the Whispering Pines Supper Club. The smiling woman behind the cake is Cynthia “Shag” Harrell, the hostess who taught black and white patrons the latest dances from Harlem—often adding a few steps of her own. Many people believe she was the first to develop what became the Carolina Shag.

Photo by Keith Phillips

It’s the summer of 1950, another Saturday night in Myrtle Beach. Waves crash. The boardwalk buzzes with tourists. But past the hustle and bustle of Ocean Boulevard, in a racially segregated neighborhood known as Booker T. Washington (BTW), the real party is going down on Carver Street, at a nightspot known as Charlie’s Place.

Established in 1937 by Charlie and Sarah Fitzgerald, Charlie’s Place consisted of the Whispering Pines Supper Club, the couple’s little house, and the Fitzgerald Motel—a two-row motor lodge that was listed in the Negro Motorist Green Book travel guide.

Whispering Pines was no mere juke joint. Waiters wore starch-white shirts and styled their hair into conk pompadours. The hostesses sported classy dresses and victory rolls. A loaded jukebox played the newest R&B. The stage was packed with the best acts touring the Chitlin’ Circuit, and patrons of all races raised glasses together, letting their backbones slip into a dance—all under the nose of Jim Crow laws.

Today, the city of Myrtle Beach has restored what’s left Charlie’s Place to tell the forgotten story of how the Fitzgeralds made a glamorous place where blacks and whites could dance together, how Shag dancing was quite possibly born on the Whispering Pines dance floor, and how the harsh realities of the segregated South brought it all crashing down.

Open for business

“Carver Street was the business district of BTW,” says Mary “Cookie” Goings, director of Myrtle Beach’s Neighborhood Services Department. “There were houses and apartments interspersed with restaurants, a pool hall, a barber shop. There were bars and clubs like Patio Casino and Little Club Bamboo, but in the middle of it all was Charlie’s Place.”

Myrtle Beach tourist hotels like the Ocean Forest and Patricia Manor were “whites only,” but the hotel staff were primarily African Americans, says Matthias Grissett, a coordinator for Myrtle Beach Neighborhood Services who gives tours of the restored property. When work was done, the hotel employees would head to Charlie’s Place. So did the top touring musical acts of the day, who played midnight shows at Whispering Pines and stayed in the motel.

Charlie’s Place hosted a who’s who of black entertainers—Ray Charles, The Drifters, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Etta James, Louis Jordan, The Ink Spots, Otis Redding, Big Joe Turner, and Percy Sledge, to name a few. White audiences flocked to see the late shows on Saturday nights.

Originally, the Whispering Pines pavilion and dining room were reserved for black patrons. Visiting white customers sat in balconied sections, but that arrangement didn’t last long, according to local musician and community leader Herbert Riley, who helped spur the renovation of Charlie’s Place before he passed away in 2019.

“The whites come down there to dance, and party … like it wasn’t nothing,” he recalled in an interview cataloged by the Library of Congress for the American Folklife Center. “A lot of lasting friendships were made.”

A dance is born

Charlie Fitzgerald was born Lucious Rucker in New York City. He and Sarah moved to Myrtle Beach in 1935. A shrewd businessman, he also owned a gas station and cab company. He lent money to black and white people, investing all over town, and became one of the Grand Strand’s richest African Americans.

The couple also brought Cynthia “Shag” Harrell to the supper club as a hostess. Originally from the South, Harrell ventured to the clubs in Harlem to learn new dances. She brought these moves back to Charlie’s Place and didn’t shy away from teaching them to white dancers. Soon, everyone was abuzz about a popular new dance developed by “Shag on the Hill.”

The dance migrated away from BTW and got transplanted in Cherry Grove, North Myrtle, and Carolina Beach. In each new place, its origins muddled, local dancers would lay claim to its invention, and eventually, the Carolina Shag would become the official state dance.

A terrible parade

In 1950, angry political rhetoric about “race mixing” emboldened the local Ku Klux Klan to take aim at Charlie’s Place. One hot August night, police cleared the roads as a procession of 25 vehicles, carrying about 60 Klansmen, paraded through the neighborhood.

Just before midnight, the Klansmen fired more than 500 bullets at Charlie’s Place. In the chaos, one Klansman was shot in his back and killed by another Klansman.

Clubgoers fled in all directions. Charlie wielded a pistol and tried to defend his club, but he was disarmed and thrown into the trunk of a car as attackers entered the building with bats and smashed the jukebox. Shag Harrell was injured along with another employee. The attackers drove Charlie out to a remote location and beat him viciously before he managed to scramble away into the woods under a hail of bullets.

After the attack, BTW crumbled and people left. White dancers stayed away. The FBI investigated the raid, and Time magazine wrote a feature about it. Thurgood Marshall came with the NAACP and represented Charlie in a federal case. Although some Klansmen were arrested and charged with conspiracy to incite mob violence, a grand jury cleared them.

Months after the raid, Charlie and Sarah pieced the club back together. The crowds slowly came back, but the magic was fading.

In 1955, Charlie died of lung cancer at the age of 49. Sarah kept the club going for another 10 years, but integration spelled the end of Charlie’s Place, says Goings. “Once African Americans gained access to everywhere—restaurants, clubs, and beaches, the money-making power of black neighborhoods left, too.”

A new plan

Whispering Pines was abandoned and torn down in the late 1960s, but the little house and the motor lodge that hosted so many famous musicians remained, abandoned and neglected until 2015, when a Myrtle Beach city employee found an article about Charlie’s Place and began asking around. The inquiries led to Herbert Riley, a member of the Carver Street Committee. Riley knew all about Charlie’s Place—his mother had been friends with Sarah. Soon he and other civic leaders made it their mission to save and renovate the site.

Now owned by the City of Myrtle Beach, Charlie’s Place is a community venue and living history monument that has hosted the Myrtle Beach Jazz Festival and Juneteenth celebrations. As a nod to Charlie and Sarah’s business acumen, four rooms in the revitalized motel building are set aside as “business incubators” and rented out to local companies. Visitors can also arrange a guided tour of the facilities that include restored motel rooms filled with musical instruments and memorabilia from the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.

Both Goings and Grissett grew up in neighborhoods near Charlie’s Place, and they take personal pride in sharing the story. “To be in this neighborhood, serving it in a different capacity, has been a Godsend,” Grissett says.

“It’s our responsibility to share this place that’s so rich in history. All the good, but also the bad stuff,” Goings says. “This little place is full of music and love. We are the product of it, part of it all, and we’re trying to share it, to teach that history honestly.”

___

Get There

Charlie’s Place is located at 1420 Carver Street in Myrtle Beach.

Hours and admission: Free tours are available on Tuesday and Friday from 12:30 to 2 p.m. or by appointment.

Details: Call (843) 918-1056 or visit cityofmyrtlebeach.com/i_want_to/find/charlies_place.php.