1 of 7

Snakes Alive!

Whit Gibbons with the University of Georgia's Savannah River Ecology Laboratory gives us an up-close look at two of South Carolina's venomous snakes.

2 of 7

Copperhead

Scientific name: Agkistrodon contortrix

ID tips:

- Solid, coppery shading on the head.

- Dark, hourglass-shaped bands on a light-brown body.

- Baby copperheads have the same characteristics, along with a yellowish or green-colored tail.

Adult size: 2–3 feet; maximum over 4 feet

Photo by J.D. Wilson

3 of 7

Cottonmouth aka water moccasin

Scientific name: Agkistrodon piscivorus

ID tips:

- Wide, dark bands across an olive-colored body, though some adults may appear solid brown or black.

- Babies are brightly banded with yellow-tipped tails and are often mistaken for juvenile copperheads.

- Cotton-white mouth lining.

Adult size: 2–4 feet; maximum over 5 feet

Photo by J.D. Wilson

4 of 7

Eastern coral snake

Scientific name: Micrurus fulvius

ID tips:

- A beautifully colored snake with alternating red, yellow and black rings that encircle the body entirely.

- The front of the head is black followed by a wide yellow ring, then a wide black ring.

- Red rings on the body touch yellow rings.

Adult size: 1½–2 feet; maximum 4 feet

Photo by J.D. Wilson

5 of 7

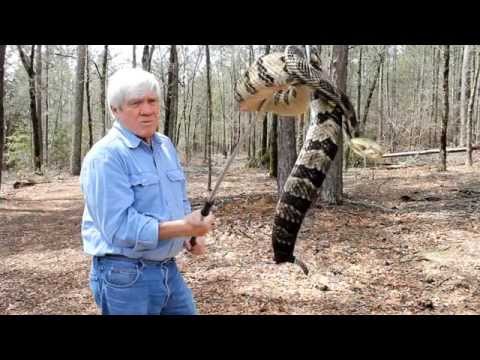

Timber rattlesnake aka canebrake rattlesnake

Scientific name: Crotalus horridus

ID tips:

- Gray or light-brown body with black chevrons across back.

- Occasional individuals are yellowish or almost black.

- Tip of tail looks like black velvet, and rattles may be present.

Adult size: 3–5 feet; maximum more than 6 feet

Photo by J.D. Wilson

6 of 7

Eastern diamondback rattlesnake

Scientific name: Crotalus adamanteus

ID tips:

- Brown body with dark diamonds bordered in yellow or white.

- White stripes in front of and behind the eye on each side of the head.

Adult size: 4–6 feet; maximum 7 feet

Photo by J.D. Wilson

7 of 7

Pigmy rattlesnake aka ground rattlesnake

Scientific name: Sistrurus miliarius

ID tips:

- Gray or brownish-gray body with dark blotches down the back and on each side.

- A tiny set of rattles at the end of the tail.

- Babies have a yellowish tail tip and are small enough to coil up on a silver dollar.

Adult size: 1–2 feet; maximum 2½ feet

Photo by J.D. Wilson

South Carolina is home to 38 native species of snakes. Six of those species are venomous.

Do the math. If you see a snake in the wild this summer, chances are it’s completely harmless to humans, and even venomous snakes aren’t interested in biting you. In fact, seeing snakes in the wild should be something to celebrate. It means the local environment is healthy.

As a biologist specializing in reptiles, this is the message I convey to people whose first reaction to any snake is to kill it. Killing a snake is almost always unwarranted, and the attempt is often far more dangerous to the human than it is to the snake. Most bites occur when people pick up or try to kill a reptile, and these bites can be avoided simply by allowing the snake to go on its way.

Giving all snakes a wide berth while at the same time enjoying them is always the best policy, and that’s especially true for the six venomous species found in South Carolina.

Copperhead

Copperheads are found across the entire state and in virtually all habitats with the exception of aquatic areas. Their secretive nature, extraordinary camouflage and mostly nocturnal behavior make them hard to spot. Without question, copperheads will see far more people this summer than people will see copperheads.

Agkistrodon contortrix is the least dangerous of the large venomous snakes in South Carolina due to a limited supply of venom and a reduced potency. In one study, copperheads delivered only half as much venom as cottonmouths, and their venom was only half as powerful drop for drop. This does not mean that a copperhead bite is harmless. Like any venomous snakebite, it should be treated by a doctor immediately.

When copperheads strike at people, they often do so with mouths open and at a distance much too far to be effective. Biologists presume this behavior to be a warning and not a serious attempt to bite.

Cottonmouth aka water moccasin

The cottonmouth is the most common venomous snake around water. The bite of a cottonmouth can be fatal, but the snake’s aggressiveness is more smoke than fire.

When cornered, they open their mouths, showing a cotton-white lining, vibrate their tails and give off a musky smell, but biting a person is a last resort. Studies conducted at the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory in Aiken have shown that the vast majority of cottonmouth bites occur when people pick them up, and they almost never bite when someone simply steps near them.

A cottonmouth will often emit a distinctive odor when disturbed, even when the perceived threat is several feet away. Your initial hint of a nearby cottonmouth might be what some people describe as a cucumber smell. Should you suddenly detect a strong, musky odor in a swampy area, pause and look carefully for a cottonmouth.

It’s easy to confuse harmless watersnakes for cottonmouths. Nonvenomous watersnakes can grow large and present the arrow-shaped head that many people associate with cottonmouths. Sadly, this bluff has a downside. Many watersnakes are needlessly killed by people who think they have eliminated a cottonmouth.

Eastern coral snake

A relative of the cobra, coral snakes inject potent venom that can kill an adult human. In South Carolina, coral snakes are small, rare and unlikely to bite a person unless picked up. Perhaps the greatest danger is to children, who might be tempted to handle this brightly colored reptile.

The age-old ditty “Red, yellow, kill a fellow; red, black, okay Jack” describes the distinction between the venomous coral snake and the harmless scarlet kingsnake. The rhyme refers to the coral snake’s red rings, which touch only yellow ones and are never adjacent to black. In contrast, the red rings of the scarlet kingsnake touch only black and never yellow. My advice: If you need this rhyme to distinguish between the species, you have no business picking up the snake in the first place.

Coral snakes inhabit most of the coastal plain, and they are generally associated with dry, sandy habitats of pine and scrub oaks. The distribution of coral snakes is spotty throughout their range, but when they do occur in an area, they are usually much more common than perceived, because they spend most of their lives underground.

Timber rattlesnake aka canebrake rattlesnake

Crotalus horridus, better known as the timber rattlesnake in the mountains and the canebrake rattlesnake on the coastal plain, is South Carolina’s most common and wide-ranging rattlesnake species. These big snakes are very much at home in every type of terrain from hardwood and pine forests to coastal islands. Although a terrestrial species, canebrake rattlers have been observed swimming across large rivers or lakes.

During the late-summer and early-fall mating season, large male canebrake rattlesnakes are often spotted crossing rural roads in the Lowcountry. In the Upstate, timber rattlesnakes may congregate in dens from autumn to spring.

Bites from a canebrake or timber rattlesnake can be extremely serious because of their potential for injecting a large quantity of venom. However, these big rattlesnakes work hard to avoid people. They rely on natural camouflage to blend in with the forest floor and will escape into a stump hole if given the chance. Recent research in South Carolina has documented that the vast majority of these snakes do not even rattle, a behavior that would only draw attention.

Eastern diamondback rattlesnake

The largest and most dangerous snake in South Carolina, the eastern diamondback rattlesnake can grow up to 7 feet long. This species sports very long fangs and has the ability to inject a large quantity of highly potent venom. Bites can be fatal and should be treated at once by a doctor.

The diamondback is restricted to the coastal third of the state and is most abundant in areas sparsely inhabited by people, including offshore islands. When coiled on the ground in their typical habitats, including pine stands, tall shrubs and grasses, eastern diamondbacks are very hard to spot, and I’ve seen people walk unknowingly within inches of them. Despite their ability to deliver a lethal bite, an eastern diamondback whose cover has been blown will first try to escape into a burrow or thick vegetation if given the opportunity.

Pigmy rattlesnake aka ground rattlesnake

The smallest rattlesnake in South Carolina, the pigmy rattler or ground rattler can still deliver a painful, venomous bite that calls for immediate medical attention but is usually not life-threatening.

Pigmy rattlers are found throughout South Carolina except for the highest mountain areas in the northwest corner of the state. Their habitat can be highly variable, ranging from dry upland forests to swampy palmetto stands.

They also thrive in many suburban areas where they can go undetected. Their camouflage is so effective that most people have difficulty seeing one lying on pine straw or leaves. A homeowner might not discover these little pit vipers until one crawls into the carport seeking a place to hibernate during cool fall weather.

_____

When trouble strikes

While bites are extremely rare, what should you do if an encounter with a venomous snake goes wrong? Snake expert Whit Gibbons has this advice.

Don’t panic. Research conducted at the Savannah River Ecology Lab near Aiken shows that in defensive strikes against people, snakes inject venom only about half the time. That said, snakebite victims should always seek immediate medical treatment.

“Very few people die from snakebites in South Carolina, and you’re almost certain to be OK with proper treatment,” Gibbons says. “Get to a hospital as quickly as you can, safely.”

Treat the victim for shock. Snakebites hurt—a lot—and panic can set in quickly. “Stay calm,” Gibbons says. “Treat the person who has been bitten as if they are in shock, because they are going to be in shock.”

Throw away your old-fashioned snakebite kit. Gibbons says doctors and herpetologists no longer recommend cutting the wound to extract venom or applying a tourniquet. “Don’t do any heroic measures on your own, get to a medical doctor and let them take care of it,” he says. “There are two things to have with you when you get bitten—a set of car keys and someone to drive you to the hospital. If you have a cell phone, call ahead and let them know you are on the way.”

_____

Whit Gibbons is professor emeritus of ecology at the University of Georgia, retired senior ecologist at the Savannah River Ecology Lab and a research professor at the University of South Carolina-Aiken. He is author of more than a dozen books on snakes and other reptiles, including Snakes of the Southeast, winner of the National Outdoor Book Award. He is a member of Aiken Electric Cooperative. Range maps and size charts are from Snakes of the Southeast and provided courtesy of the publisher, University of Georgia Press.

_____

Related story

Non-venomous snakes in S.C. – Ecologist Whit Gibbons explains how non-venomous reptiles benefit the state’s environment.