1 of 2

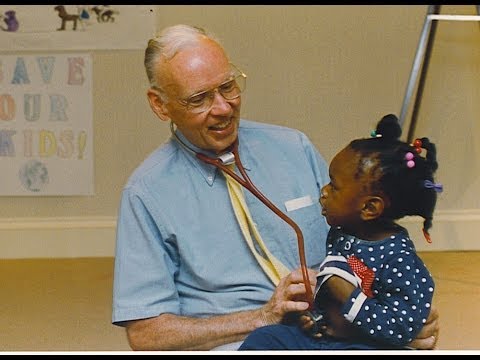

Dr. Jack McConnell founded the first Volunteers in Medicine clinic on Hilton Head Island in 1991. Today, there are 95 clinics across the nation, including 10 in South Carolina.

2 of 2

Volunteers in Medicine (American Story)

Today's American Story profiles Dr. Jack McConnell.

It all started with a simple act of kindness.

Dr. Jack McConnell was driving on Hilton Head Island one rainy day when he stopped and offered a ride to a man walking alongside the muddy road. While driving him to a work site, the doctor learned that the man had a pregnant wife. McConnell asked him if he and his family were getting health care. The answer was no, they had no insurance.

McConnell was surprised to learn that thousands of his fellow islanders lacked insurance. Despite Hilton Head’s reputation as a wealthy retirement community, it’s also home to thousands of tourism and service-sector workers who don’t earn benefits and often lack access to care. The doctor, who was born in the coal-mining town of Crumpler, W.Va., harkened back to his childhood. Every night at the dinner table, his minister father would ask his children, “What have you done for someone today?”

McConnell had been a biomedical researcher at Johnson & Johnson, where he directed the development of Tylenol, created the first Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) system, and helped draft federal legislation that led to the creation of the Human Genome Project. He and his wife retired to Hilton Head in 1989, where he intended to spend his days golfing, but after picking up the man in the rain in 1992, he had a new plan: recruit retired and practicing health care professionals to start a free clinic.

Volunteers in Medicine (VIM) opened its doors on Hilton Head in 1993, and McConnell’s clubs stayed in the garage. Today, there are 95 VIM clinics operating in across the nation, including 10 in South Carolina—all of them offering free, first-rate health care to patients in need.

“I thought I’d start one clinic and go back to playing golf,” he jokes. “That didn’t work out so well.”

Walk-ins welcome

On most mornings, the line starts forming at the Hilton Head clinic about 8 a.m. There are seniors, young couples and parents with little ones waiting to sign in. During a typical morning clinic session, the staff will see more than 50 walk-in patients and another 60 to 80 patients who have appointments.

The clinic primarily serves the working poor. To be treated at the Hilton Head clinic, patients must live or work on Hilton Head or Daufuskie islands and family income must be less than 200 percent of Federal Poverty Guidelines. Income and residency verification are required. None of the almost 15,000 patients treated annually are charged a fee, though many contribute what they can to the donation jar in the reception area.

When the clinic doors open at 8:30 a.m., the 30-seat reception area fills up quickly as doctors, nurses and volunteers get to work. Soon, the hallways, exam rooms, blood lab, dental clinic, pharmacy, X-ray room and an outpatient surgery center are abuzz with the nonstop activity one might expect from a small hospital.

Over the years, the mission has shifted from acute care to managing wellness, says Dr. Frank Bowen, the executive medical director. For example, the clinic now has a women’s program that focuses on mammograms, pap smears and other preventative diagnostics. To date, the program has performed about 2,500 mammograms and detected 20 cases of breast cancer. All but one survived.

“We started out largely as an ‘I’m sick’ walk-in clinic,” Bowen says. “But we’re moving toward being a ‘That’s where I’ll go to stay healthy’ clinic. Just because a person is poor does not mean that they can’t be healthy.”

Healing hands

The Hilton Head clinic boasts an impressive roster of more than 100 volunteer doctors representing 23 specialties. They include a diabetes expert who taught at Harvard University, an orthopedist who taught at Yale University, doctors from Johns Hopkins University, and doctors who worked at Mayo Clinics around the country.

“We even have a doctor who practices in Chicago in a hospital emergency room who drives here once a month to volunteer,” Bowen says.

Dr. James Breen, an obstetrics and gynecology doctor who volunteers at the clinic, counts himself as blessed to practice at VIM. “It’s selfish in a way,” he says. “I think it’s actually more beneficial to our doctors than to our patients. You’ve dedicated your life to medicine and then you’re just expected to retire. I am so thankful that I get to do the things I love to do.”

In addition to the M.D.s, there are more than 90 volunteer nurses, 20 mental health counselors, 30 dentists and 300 lay volunteers who help out at the clinic. All told, volunteers contribute more than 51,000 hours of labor per year.

Even with all the free labor, it’s not cheap to run a free medical clinic, Bowen says. VIM relies on donors, grants and local fundraising to meet its $1.8 million annual budget. Donations are tax deductible, and 89 cents for every dollar donated goes directly to patient care. The clinic also stretches those funds with the help of the Hilton Head community. Local churches provide rides to and from the clinic, and grateful patients help clean and maintain the building.

Even private health-care providers pitch in. In September 2010, Hilton Head Hospital donated $75,000 and agreed to support the clinic with advanced medical and surgical procedures, but hard economic times have created a budget shortfall, and the need for service continues to grow.

“We’re almost a victim of our own success,” Bowen says. “We’re looking at ways that we can save money and ways that we can generate more funds.” The one option that’s not on the table: “We’re not going to cut the number of patients we see.”

Culture of caring

In South Carolina, there are now a total of 10 clinics operating on the VIM model, including The Community Medical Clinic of Aiken County, the Good Shepherd Free Medical Clinic of Laurens County in Clinton, the Palmetto Volunteers in Medicine Clinic in Rock Hill and the Free Medical Clinics in Columbia, Johns Island, Newberry, Taylors and Woodruff. As this issue went to press, the state’s newest VIM clinic—serving Bluffton and Jasper County—was scheduled to open April 29.

The core principle of all VIM clinics is a "Culture of Caring,” which posits that every person deserves to be treated with dignity and respect, but by offering preventative care to uninsured, free clinics like VIM and low-cost Community Health Centers (see sidebar below) also save taxpayers millions. It costs about $68 to treat a patient in a free clinic, according to the South Carolina Free Clinic Association. The cost of the same care in a hospital emergency room: $1,600.

Now consider that 760,000 South Carolinians —approximately 1 in 4 of the state’s residents— don’t have health care, according to U.S. Census data. And with a struggling economy, demand for free and low-cost health care is growing in South Carolina and across the nation, says Amy Hamlin, executive director of the national VIM Clinic Alliance.

“There is a huge surge in demand right now,” she says. “People are working for less money or have lost their jobs. But at every clinic, we see the local communities respond with caring and compassion.”

On Hilton Head Island, Dr. McConnell is now fully retired and no longer involved in the day-today operations of the clinic that started it all, but he still visits from time to time to greet patients and thank the staff and volunteers who continue the tradition of kindness and caring.

“There is a huge need for something like this,” McConnell says. “We need more people to step up and say, ‘We can help you. We will help you.’ ”

To find the nearest free clinic or additional health resource for you, click here.

_____

Related story

Good medicine - Meet Dr. Raymond Cox, the new executive director of the Volunteers in Medicine clinic on Hilton Head Island.