1 of 8

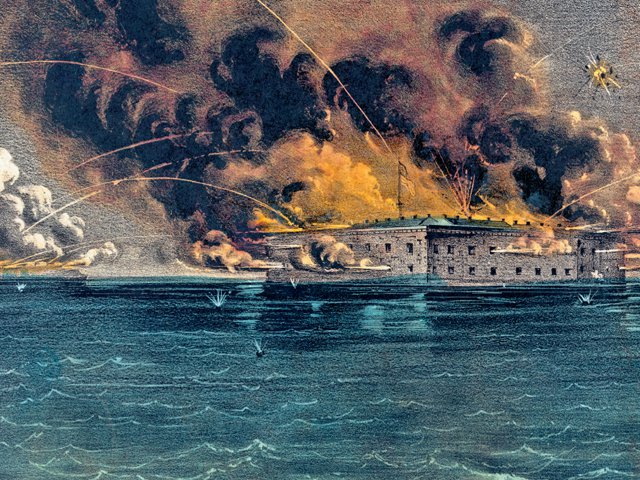

Bombardment of Fort Sumter, Charleston Harbor.

Published by Currier & Ives/Library of Congress

2 of 8

Exhibits, including “African Passages” at the Fort Moultrie visitor center explore the cultural and military aspects of the war.

Photo by Milton Morris

3 of 8

The Warren Lasch Conservation Center is a working laboratory that opens its doors to visitors on weekends. Interactive displays allow kids of all ages to experience what it was like to be a crewman on the H.L. Hunley.

Photo courtesy of Friends of the Hunley

4 of 8

Visitors to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center can observe the hull of the submarine inside its 90,000-gallon conservation tank and learn about the latest archaeological findings during weekend tours offered on Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Sundays from noon to 5 p.m. The lab is located at 1250 Supply St. in North Charleston. Regular admission is $12, with children under 5 admitted free. For more information, contact Friends of the Hunley at (843) 743-4865, ext. 10, or visit hunley.org.

Photo by Mic Smith

5 of 8

The Penn Center stands on the site of the South’s first school for freed slaves, which opened on St. Helena Island in 1862 during Union occupation. Today it serves as a center for preserving and interpreting Gullah culture.

Photo by Keith Phillips

6 of 8

Visitors to Redcliffe Plantation State Historic Site can explore the grounds for a glimpse of what life was like in antebellum South Carolina.

Photo courtesy of Redcliffe Plantation

7 of 8

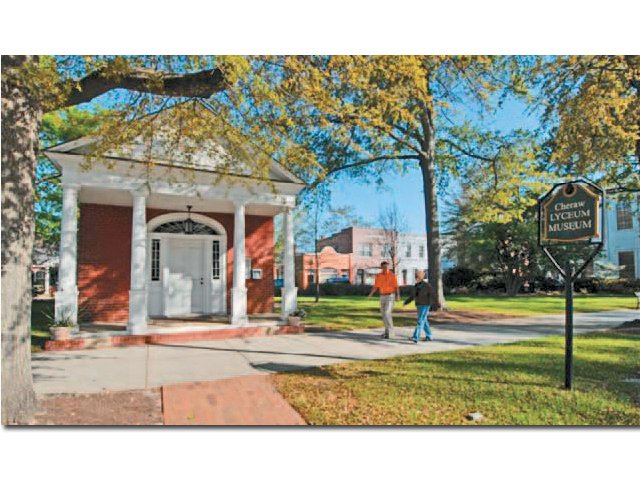

Cheraw’s Lyceum survived Sherman’s occupation and today serves as the town museum.

Photo courtesy of SCPRT

8 of 8

Tours of the Burt-Stark mansion include the men’s parlor where Jefferson Davis officially disbanded the Confederate government on May 2, 1865, declaring, “All is indeed lost.”

The fiery voices of secession had carried the day. Reveling in South Carolina’s newly declared independence from the Union, Gov. Francis W. Pickens demanded that federal troops garrisoned in Fort Sumter, one of several outposts guarding Charleston Harbor, abandon their position. Rebels controlled all of the other coastal defenses, including Fort Moultrie, on the southern tip of Sullivan’s Island, and Fort Johnson, on the northern end of James Island, and under secession flags, Confederate troops trained their cannons on Sumter’s brick enclosures.

The tension broke at 4:30 a.m., April 12, 1861, when a 10-inch mortar round fired from Fort Johnson began a 34-hour exchange of artillery fire that lit up the sky and marked the first battle of the U.S. Civil War.

The war that forever changed the course of our nation began—and some say officially ended—right here in South Carolina. To mark the 150th anniversary of the conflict, South Carolina Living presents this travel guide to our state’s most significant Civil War sites, parks and museums. From the opening salvo against Fort Sumter in Charleston, to the collapse of the Confederate government at the Burt- Stark Mansion in Abbeville, to the dawn of a new era for former slaves at the Penn Center on St. Helena Island, these unique places provide a living sense of history and a way for families to enjoy a day together exploring modern-day South Carolina.

CHARLESTON: WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

As the Confederate assault on Fort Sumter wore on through its first day, jubilant Charlestonians flocked to the waterfront streets to watch the fireworks. Some sipped cocktails from their balconies, unaware that the events unfolding before them were the start of what would become one of the bloodiest conflicts in human history. The battle ended when the federal troops, outgunned and low on provisions, surrendered the fort, but Charleston paid the price for rebellion over the next four years as the Union Navy blockaded and bombarded the city until the war’s end in 1865.

Fort Sumter National Monument

Located on a man-made island at the mouth of Charleston Harbor, Fort Sumter is surprisingly serene, especially when you consider its violent history. “It’s such a beautiful, scenic place to visit it’s hard to imagine what was happening then, but you can see exactly where it all took place, and it really sticks with you when you stand out there and feel it,” says Michael Allen, a National Park Service historian.

Fort Sumter, Fort Moultrie on nearby Sullivan’s Island, and a visitor Education Center on Liberty Square in downtown Charleston, are all part of the Fort Sumter National Monument, but each is a distinct attraction in its own right. Displays at the education center walk visitors through the events leading up to the firing on Fort Sumter and include a stunning 20-by-36-foot replica of the flag that flew over the fort during the battle. Fort Sumter itself is accessible by ferry boats that leave from the center and from Patriots Point. Rangers greet the boats dockside to narrate the events that took place in 1861, then visitors are free to roam the grounds guided by interpretive exhibits describing the fort’s unique place in history.

Fort Moultrie, accessible by car, has its own visitor center documenting the fort’s use from the Revolutionary War period all the way up to World War II. Exhibits also explore the sometimes gritty reality of the state’s history and the build-up to the Civil War. A highlight is the dramatic “African Passage” exhibit, a heart-wrenching examination of the slave trade including the meticulously documented story of Priscilla, a 10-year-old girl taken captive in Sierra Leone and shipped to America in 1756. Also on site is a monument—a simple bench put in place by the Toni Morrison society—marking the very spot where at least one-fourth of all the enslaved Africans brought to America first landed.

Telling the full history of the events surrounding the war is important, Allen says, even if it’s sometimes painful.

“The National Park Service sees all this as an opportunity to meet our goal of telling the broad-based story of what happened here,” he says. “We’re working with partners who have come together to tell the story of what happened in the battlefield, who wore the gray and blue uniforms, who pulled the lanyard to fire the first cannon, but also those on the home front, who managed affairs while relatives were away, and the role of the African-Americans whose freedom came out of this.”

Fort Sumter National Monument is open year-round except for New Year’s Day, Thanksgiving and Christmas. Hours vary by site and season. For details, visit nps.gov/fosu or call (843) 883-3123. For Fort Sumter ferry information, visit fortsumtertours.com or call (800) 789-3678.

Warren Lasch Conservation Center

One of the great mysteries of the Civil War—the fate of the Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley—has puzzled historians ever since the night of Feb. 17, 1864, when the human-powered craft became the first submarine to sink an enemy ship in combat. Under the command of Lt. George Dixon, an eight-man crew exploded a torpedo beneath the Union warship USS Housatonic, but the victorious sub never returned to port.

In 2000, marine archeologists raised the intact Hunley from the muddy seafloor and placed it in a 90,000-gallon conservation tank located in the former Navy yard in North Charleston. In the years since, researchers have recovered and buried with military honors the remains of the crewmen, restored numerous artifacts and rewritten the history books on how the sub was constructed and operated. But they have yet to determine exactly why it sank.

The search for answers continues, funded in part by admission fees from weekend visitors to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center. A highlight of the behind-the-scenes tour is peering down into the tank that holds the historic vessel.

“One thing that strikes you immediately is how small it is and that eight men were able to squeeze in there and power it by hand,” says Kellen Correia, executive director of Friends of the Hunley, which conducts weekend tours of the facility. “And then there’s the emotional component, as you think of the bravery that allowed them to get in there and do what they did.”

Interactive exhibits detail the operation of the sub, what historians think happened that fateful night and the biographies of the crew. Among the remarkable artifacts on display is the bent gold piece found with the remains of Lt. Dixon. A bullet struck the coin during the battle of Shiloh in 1862, sparing Dixon’s life, and he kept it for the rest of his numbered days as a good luck charm bearing the ironic inscription, “My Life Preserver.”

Visitors to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center can observe the hull of the submarine inside its 90,000-gallon conservation tank and learn about the latest archaeological findings during weekend tours offered on Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Sundays from noon to 5 p.m. The lab is located at 1250 Supply St. in North Charleston. Regular admission is $12, with children under 5 admitted free. For more information, contact Friends of the Hunley at (843) 743-4865, ext. 10, or visit hunley.org.

_____

THE LOWCOUNTRY: LEARNING TO BE FREE

Beginning with the Battle of Port Royal Sound in November 1861, the Civil War ran a violent, tumultuous course through the Lowcountry. Beaufort was the first Southern city occupied by the Union, and the U.S. Navy soon established its southern Atlantic blockade headquarters on Hilton Head Island. Slavery was abolished on the Sea Islands, followed shortly by the birth of one of the most significant African-American history sites in the country, the Penn Center.

Penn School National Landmark Historic District

Shrouded by ancient oaks and tucked away on a still-rural stretch of St. Helena Island, the Penn School National Landmark Historic District is the site of the South’s first school for freed slaves. The 50-acre campus operated as a school until 1953, when it became a conference facility. During the Civil Rights era, it famously hosted strategic retreats led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Today, it also serves as a Gullah cultural center dedicated to preserving the language and traditions handed down from former slaves to their modern descendants.

“Our visitors often tell us they get a sense of awe when they come here, both because they never realized there’s so much here at the Penn Center itself, and because it’s their first exposure, many times, to real Gullah culture and language,” says Rosalyn Brown, the center’s director of history and culture.

Brown points guests to the York W. Bailey Museum, which shares the cultural legacy of the Gullah people and offers a gift shop featuring sweetgrass baskets, quilts, Gullah memorabilia and books. While you’re there, make sure to see the ETV-produced film documenting the Penn Center’s history. Also onsite: the Laura M. Townes Archives and Library. Open by appointment only, it features one of the oldest collections of African-American photographs in the country.

Visitors to Penn Center also can participate in the Gullah praise tradition of community sings held every third Sunday from September to May, as well as the annual Penn Center Heritage Days celebration during the second weekend in November.

The Penn Center is open daily, except Sundays, from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. For details, visit penncenter.com or call (843) 838-2474.

Robert Smalls Monument

Robert Smalls escaped slavery in December 1862 by seizing a Confederate steamer, sailing it past rebel sentries in Charleston Harbor and delivering it to the U.S. Navy. After serving with distinction as a Union officer, he became one of the first African Americans elected to Congress. A monument to Smalls marks his burial site on the grounds of Tabernacle Baptist Church at 911 Craven St. in Beaufort. His former home at 511 Prince Street is on the National Register of Historic Places and makes for a nice photo op, but it’s a private residence so there are no tours.

The Tabernacle Baptist Church grounds are open daily during daylight hours. For details, visit beaufort-sc.com/history or call (843) 524-0376.

_____

THE SAVANNAH RIVER VALLEY: SHERMAN'S FIRST STOP

After burning Atlanta and capturing Savannah, the Union Army under Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman turned its attention to the capture of Columbia in the early days of 1865.

Rivers Bridge State Historic Site

Sherman’s march into South Carolina encountered its first serious resistance on the banks of the Salkehatchie River at what is now Rivers Bridge State Historic Site near Ehrhardt. Here, in the deep, swampy woods, the still-intact earthen fortifications bear silent witness to the fierce battle that raged on Feb. 2–3, 1865. Rivers Bridge is the only stateprotected Civil War battlefield site in South Carolina, and an interpretive trail takes visitors along the silent breastworks where men on both sides fought and died.

“This is one of those special places where you can get a sense of reverence and awe just thinking about what happened here and the tragic loss on both sides,” said Phil Gaines, director of the S.C. State Park Service. “Maybe it’s the remote location and the deep woods and swamps, but sometimes you can just feel the desperation the Confederates must have felt and the wonder the northern troops must have felt, seeing such a different place than where they were from.”

Rivers Bridge State Historic Site is open daily from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Admission is free. For details, visit southcarolinaparks.com or call (803) 267-3675.

Redcliffe Plantation State Historic Site

"Cotton is king!" roared South Carolina Senator James Henry Hammond in 1858 as the halls of Congress shook and war drew ever nearer. Hammond, also a former governor, knew a thing or two about cotton from his life at Redcliffe, his plantation near the Savannah River where he experimented with crops and planted uniform rows of magnolia trees that still line the lane to the manse. Donated to the state in 1973, the Greek Revival house and grounds—including preserved slave quarters and an heirloom garden—are open year-round offering a variety of seasonal interpretive programs.

Redcliffe Plantation State Historic Site is open Thursday to Monday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. For details, visit southcarolinaparks.com or call (803) 827-1473.

_____

COLUMBIA: THE BURNING QUESTION

This much we know: Union troops were in control of Columbia on the night of Feb. 17, 1865, when a cotton-fueled fire leveled much of the city. Whether the fire was accidental, as Union soldiers claimed, or vengeance, as Confederates alleged, has never been determined for sure. Today, however, the capital city is an ideal place to learn more about the Civil War.

South Carolina State Museum

While the life-size replica of the H.L. Hunley has long been a popular exhibit at the South Carolina State Museum, the curators are marking the sesquicentennial by adding new Civil War sections each year for the next four years.

The first exhibit, “The Coming of the Civil War,” focuses on the causes and defining moments leading to the outbreak of hostilities. It includes such items as a table and chairs from the secession convention at Columbia’s First Baptist Church, a diorama of a secession ball in Charleston and a copy of the Ordinance of Secession.

“Items like an 1860 Palmetto Flag really give you a feel for the new sense of independence from the rest of the union that South Carolinians were feeling in those days,” says Fritz Hamer, the museum’s curator.

Other items, such as a 10-inch mortar shell very similar to those fired at Fort Sumter, speak to their deadly serious intent to secure that independence.

The next exhibit opens July 22. “The Civil War in South Carolina: Duty to State and Family” focuses on the formation of military units and their service and sacrifice throughout the war. “We’ll also have a section on African-Americans from South Carolina, on where they fought for the Union and those who worked for the Confederacy,” Hamer says.

The South Carolina State Museum is open year-round Tuesday to Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Sundays from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. The museum is also open on Mondays from Memorial Day through Labor Day. For details, visit southcarolinastatemuseum.org or call (803) 898-4921.

_____

MIDLANDS TO THE PEE DEE: THE UNION ADVANCES

Done with Columbia, Sherman’s army advanced toward North Carolina roughly following the route that is now U.S. 1, and passing through Camden, Hartsville and Cheraw en route.

The Cheraw Lyceum

Sherman himself stayed in the Chesterfield County town of Cheraw for several days in early March of 1865, where his men, town history has it, celebrated Lincoln’s second inauguration by drinking and looting. Although the visit was punctuated by an accidental explosion of captured Confederate gunpowder that razed most of the downtown business district, more than 50 antebellum buildings are still standing.

One of the surviving buildings, the Lyceum, was occupied by both armies during the war and is now the town museum, operated by the Chamber of Commerce. Among the stories it tells is that of the CSS Pee Dee, a gunboat that was scuttled in the nearby Great Pee Dee River after covering the Confederate retreat ahead of Sherman’s arrival. The Lyceum was the town library during the war and the path of some of the Union soldiers could be followed into North Carolina by the books they abandoned along the way.

The Cheraw Visitors Bureau/Chamber of Commerce at 221 Market St. is open weekdays from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. For details, visit cheraw.com or call (843) 537-8425.

_____

ABBEVILLE: WHERE THE WAR ENDED

The armed conflicts in South Carolina all took place below the Fall Line, but the Piedmont hosted one of the war’s most significant moments.

While historians consider Robert E. Lee's surrender at Virginia’s Appomattox Courthouse on April 9, 1865, to be the end of the war, Abbeville's Burt-Stark Mansion stakes its claim to being where the Confederate government officially disbanded.

On the run after the fall of Richmond, Va., Confederate President Jefferson Davis stopped at the Greek revival house on May 2 en route to Mississippi. He began the day intending to fight on, but that afternoon a group of his Cabinet members and brigade commanders finally convinced him that the South was defeated.

"'All is indeed lost,' he finally brought himself to say," says Katy Tilley, a member of Little River Electric Cooperative and chairman of the Abbeville Historic Preservation Committee. "It was right here in the men’s parlor."

A distraught Davis dismissed his Cabinet, sent the troops accompanying him on their way, then retired to an upstairs bedroom to rest before continuing his journey. The bed he slept in is on display and visitors touring the house and grounds can easily imagine the events of the war’s final moments, Tilley says. "It was a great struggle and it indeed, had come to an end. Right here in Abbeville."

The Burt-Stark Mansion is open Friday-Saturday, 1 p.m. to 5 p.m., other times by appointment. Admission is $10 per person. For details, visit burt-stark.com or call (864) 366-0166.

_____

Related Stories

Living history (South Carolina’s Civil War reenactments bring the 1860s to life)

Seeing the elephant (A first-time reenactor reports from the Battle of Charleston)

Ride to the sound of the guns (Your guide to the state's top Civil War living history weekends)

Reload and fire (Bonus video from the 2013 Battle of Aiken)

The Slave Dwelling Project (Civil War reenactor Joseph McGill’s project to preserve the American history represented by slave dwellings)

S.C. Civil War historic sites (Your travel guide the state’s most significant Civil War sites, parks and museums)

More S.C. historic Civil War sites

Secrets of the H.L. Hunley (Scientists are seeking new clues to solve the mystery of the famous Civil War submarine)