1 of 2

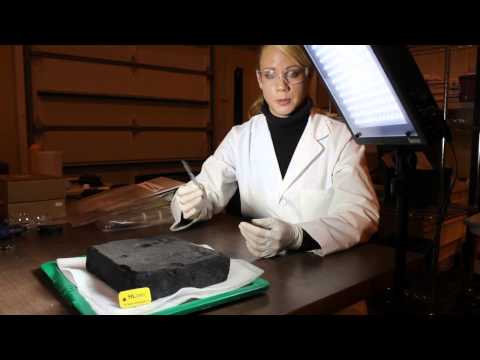

Conservator Liisa Nasanen scrapes away corrosion from a Parrott shell recovered from Fort Sumter National Monument.

2 of 2

Liisa Nasanen, a conservator working on the H.L. Hunley describes the process of treating the submarine's artifacts.

In addition to the careful excavation and analysis of the H.L. Hunley, scientists at Clemson University’s Restoration Institute are conducting groundbreaking research on better ways to restore cultural artifacts.

Objects submerged in salt water undergo dramatic changes that make them vulnerable to rapid decay when exposed to air. Properly cleaning and stabilizing artifacts for study and display is a delicate, time-intensive process, and many restoration projects are limited by a shortage of patience and funding.

Iron artifacts, like those recovered from the Hunley, are particularly vulnerable to corrosion. Chlorides in sea water bond easily to the metal at the molecular level, and the process isn’t confined to the surface material. Pockets of corrosion can form like cavities within an object. When exposed to the oxygen in air, an artifact with active corrosion can quickly disintegrate into a pile of rust, says research engineer Nestor Gonzalez-Pereyra.

“When you remove the artifact from the water and let it dry out, the combination of oxygen, humidity and salts is very energetic,” he says. “You have a very fast corrosion process.”

The traditional stabilization process for iron artifacts—soaking them in a caustic solution such as sodium hydroxide—safely extracts salts, loosens concretion and stabilizes the remaining metal, but the process takes years.

In 2003, Gonzalez-Pereyra began testing the use of a subcritical-fluid process that uses lower concentrations of caustic solutions heated to 365 F inside a pressurized chamber. When applied to iron artifacts, the Clemson researchers discovered the process could dramatically cut the treatment time from several years to just a few months or even weeks.

A 40-liter subcritical-fluid reactor at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center has been used to treat Hunley artifacts ranging from rivets and hand tools to the wrought iron blocks that ballasted the submarine.

Conservator Liisa Nasanen says artifacts treated in the chamber have been remarkably easy to clean, and they have remained corrosion-free years after undergoing the subcritical process. She was responsible for deconcreting a ballast block that was the first large Hunley artifact treated in the chamber. As she scraped away the rock-like envelope of sand, shell and corrosion byproducts, Nasanen was delighted to uncover the small details on the original surface of the artifact, including tool marks and a manufacturer's stamp.

“Deconcretion tends to be a very crude process at times,” she says. “It’s sometimes hard to find very fine details like that. To be able to do the deconcretion in a dry state gives me all the control in the world, and I can easily find and preserve features such as the tool marks.”

Working with Fort Sumter National Monument, Nasanen and Gonzalez-Pereyra have also used the subcritical process to stabilize composite metal artifacts recovered from Fort Sumter National Monument.

A second extraction process adapted by the lab for the restoration of cultural artifacts utilizes carbon dioxide under supercritical conditions. Dr. Stephanie Crette, a research scientist and the center’s interim director, has applied this technology to various specimens from the Hunley, as well as other significant marine archaeological projects. The treatment has been shown to successfully conserve organic materials such as cork without destroying the integrity of the artifact.

For more information on the restoration work underway at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, click here.

_____

Related story

Secrets of the H.L. Hunley (Scientists are seeking new clues to solve the mystery of the famous Civil War submarine)